Role Description

EMEA Software Development Center Manager

Manages operations of the EMEA Development Center which includes resource allocation, project oversight, and success indicators. He also owns the communications and management improvement program.

Background

During my stint as the Russia Marketing Center Director, I had begun to befriend a British manager who was leading a team of IT software developers down the hall from me. He mentioned that he was looking for an expat to groom his team and bring them to a higher performance level. Upon volunteering for it, he gave me the job immediately. Though it was a job in IT, a division I had worked in for five years before, the field of Windows software development was a very unknown quantity for me. There were close to 40 people on the team. Most were C#/.Net developers, some were data analysts and platform support engineers, and the rest were technical leads or managers. They also used a development process called Agile, something I had never heard of before. Nizhny reported into management in Swindon, England, Intel’s European headquarters. There, project managers, business liaisons, and business analysts resided alongside a large part of the customer base that used the solutions created by the Nizhny team. Despite the distance, Swindon and Nizhny worked fairly well together. Still, Swindon felt that Nizhny had to improve significantly in order to earn the right to do good projects, and even to exist. India was a direct competitor to Nizhny as a development center, so Nizhny had to step it up to succeed.

Though located in the hinterlands of Russia, they were actually working on one of the most important projects in the company. Intel wanted to completely rebuild their order fulfillment process. The Nizhny team had created an idea how to do it and built a prototype. The idea grew like wildfire throughout Intel and the Nizhny team suddenly gained charge of a major corporate initiative. Technically, they were up to the challenge. The programming talent, as I gradually learned, was unmatched across Intel. Unfortunately, their political and communication skills were so poor that it nearly destroyed them. I joined the team in the middle of a large crisis in the order fulfillment project.

Upon arrival, I had to meet a lot of people, learn their roles, and dive into the Agile development process. Not a lot clicked for a while, and it was frustrating and overwhelming. We created a new organizational structure that gave me their management team to report directly to me. Some of them were a bit doubtful that a non-developer could help them in any way. To some degree, they were right. I would never be giving them technical advice. I had to find ways to insert myself where useful and it usually fell to helping them get more “Intelized” and to grow their communications and political skills. They weren’t enthused by this since Russian culture usually states that genius should be discovered, not sold. The whole idea was slimy and disingenuous to them. As an example, one of the top technical people at Intel came to Nizhny to do a lecture. A large number of people from the entire site who did software development for other business groups attended. I didn’t understand a word of it, but wanted to attend since I was the site manager and usually hosted high-level guests. After the lecture, I asked him who were better developers, Russians or Indians? He chuckled and replied that Russians were 10 times better. I was impressed, but then he told me the other half of the story. Every time he visited Intel India, he would be swarmed by multiple developers offering white papers and examples of work they did. They wanted to learn how to contribute more to the company, etc., etc. Their enthusiasm was huge. However, whenever he went to Russia, nobody did this, nobody asked questions, nobody sold themselves. They just expected that everyone should know they are good and that all the best projects should go to them by default. That was the environment and culture I was dealing with in spades in my own team. I had to change that.

I wanted to step in sooner to start working on this challenge, but I was a deer in the headlights for quite a while trying to figure out how to fit in. Still, as the crisis they were falling into came to a head, I did find some areas where we could turn the situation around. The basis of the crisis was that the team was being accused of releasing poor quality code and were going too slow. The business sponsor was cutthroat and didn’t want to hear any excuses. There was even a little talk of taking the project away from them. While the charges made against us were a bit overwrought, I had to teach the team that perception is reality and that the perception of them sucked. I had to teach them how to fight back in a constructive way rather than to tell everyone to leave them alone and that everything was someone else’s fault. Victimhood was implanted deeply into the team culture and it was killing them.

As I met with some of the key players on the team more and more, some themes started emerging. First, they objected that their quality was not as bad as people were saying. I responded by saying, “Oh yeah, how do you prove that?” No answer. Then, as I learned more about how Agile development worked, I noticed that they were skipping a major step in their coding process, refactoring. I asked them why that was happening. They replied that the business wouldn’t let them do it and that nobody was listening to them. Their stakeholders also said that the team was like a black box. Nobody knew what was going on way off in Russia. I asked them how they communicated proactively and effectively. No answer. Many of these little insights started building into a clear pattern of dysfunction. Out of these discussions, I came up with three major plans of attack:

- To combat the accusations of producing poor quality code, publish code quality metrics that are agreed upon amongst stakeholders. Create an aggressive goal and report out on performance every week.

- To recover from skipping parts of their coding process, put together a proposal to rearrange the development schedule so that they could go back and refactor their code that kept getting worse and worse.

- To deal with proactive communication, create carefully crafted and timed presentations to key stakeholders to explain how the Russian team does their work, how Agile development processes contribute to their effectiveness, and how they plan to address problems.

For number 1, I told the team to go into a room without me and discuss in Russian what metrics and goals they could use to show whether they were doing a good job. I put it in their own terms. How would YOU measure yourselves? If you choose some ways to measure yourselves, what is a good number and what is a bad number? Can you automate these metrics so they are easy to report regularly and consistently? With some reluctance, they agreed to take on the task and spent a large chunk of a day figuring it out. They came back to me with several specific metrics: They were:

- Code complexity – a way to determine whether lines of code were written efficiently. (Apparently there is a way a software tool could read the code and determine this. Don’t ask me how, but it worked well. Code complexity should not exceed __%. (can’t remember the number)

- Code coverage – all code should be written with tests proving that the code works every time. (called unit testing). Needed to exceed 90%.

- Defect rate – after a release, there must be a very low rate of bugs in the product during the first 90 days of use. (can’t remember the number)

I took these numbers to our stakeholders and got agreement that these were appropriate ways to measure quality. If they met these goals, suspicion of quality problems would decline. We got our development tools to report these out daily and found out that we were significantly below goal in all of them. We opened our kimonos and showed where we were at the time. The honesty actually helped our cause more than hiding the data. Our stakeholders could see where some work could be done to improve. Week after week, we reported our numbers out and each time, they improved. Our hard evidence quickly began to fight off the negative subjective opinions and the hysteria began to cool off.

Number 2 was a hair raiser. The business sponsor only wanted more features added to the tool and only seemed to want to work harder, not smarter. He was well respected in his own circles, but considered to be a jerk to many on our side of the fence. My proposal was to stop building new features for an entire quarter so that we could clean up our code and do some redesign to make the code more stable and easier to update. To our business sponsor, this was a complete anathema. I was in a sticky situation since I was new to software development and feared I would lose my nerve as the two sides clashed. I managed to talk to enough stakeholders to get support for my idea and we were able to press the sponsor hard enough to get him to agree. Once the decision was made, I put all our best people on the job to rip through every jot and tittle of code to fix what ailed us. They spent three months on it and I could see that some remarkable results were coming out of it. Once we announced we were done and we were back to building features, we had to prove that we were moving faster with higher quality. Within a short time, it became very obvious that we achieved this. I still remember the conversation I had with the business sponsor after having so many battles with him. He said, “Ok, ok, I drank the kool-aid. I get it. You were right.” After that, we cruised and released one hell of a great software product. Intel’s CEO was even getting regular updates on its status. Eventually, he (Paul Otellini) visited Russia, met our team, and viewed our product demo and work methodology. As a result of our efforts, we completely changed the way Intel delivered product to our customers worldwide. I was extremely pleased.

For number 3, I must confess that I did most of the talking for Nizhny for a long time. Early on, there were too many critical moments that had to be managed very carefully. I’ll talk more about this one later on since I took some major steps to improve their skills in this area.

Big Changes

IT began to make some huge waves about needing to fix Intel’s SAP environment because it was a complete mess. It was so bad that SAP could not support an upgrade to a newer version since Intel had customized the current version so much. Now, a major call for all hands on deck was made. My boss took this call seriously and felt that this was the end of C#/.Net development. To head this problem off, he petitioned to have our team convert into an SAP team. He eventually achieved this and then announced this to our Nizhny team. At first, nobody knew what to think. SAP was a completely different animal. Ideally, you only configure the tool using standard features. It should not need any coding at all. Inevitably, SAP doesn’t have all the features a company wants, so they have their own programming language, ABAP, to allow for more specific customization. Our team was encouraged by this aspect since it gave them an opportunity to write more code. In the midst of this transformation, we even got a project given to us called Salesforce Automation. The only thing we had to do was get 40 people trained on an entirely new platform and technology. I was given a large budget (can’t remember the number) to bring in trainers for some things, to send them to Moscow or UK for others, or to fly in Intel people from the U.S. or India to teach us in Nizhny. It took a few months and a lot of effort to make this happen. Fortunately, one of my managers took on the task of managing this logistical nightmare and did it well.

As the training proceeded, as the understanding of the project we were given came more to light, and as the direction of IT became more clear, we started to realize that we would not be allowed to do any coding. IT made a rule that any new releases had to use the existing features in SAP and no new features could be added by writing code. This sparked a flash of panic and existential plight within our team. These guys code. That is their life. They don’t want to do anything else. If they don’t code, they don’t stay. Nobody believed it, but the reality began to brew.

Despite the trouble lying ahead, there were some very positive times while the order fulfillment project was in progress. We still had a large number of developers focused on other projects of smaller size. We developed many smaller tools that helped Intel’s Sales and Marketing Group. Our group was in high demand and so we even used an outsourcing company in St. Petersburg to do some of our work. We eventually absorbed all our resources. Each outsourced project still required some internal resources to manage it, so we did run out of capacity. This did not deter project managers in Swindon and the U.S. to continually approach us to try squeezing in another project. I had taken ownership of all resource management, so everyone called me, begging for resources. I managed all personnel in Microsoft Project and tracked each person’s time for the months ahead. Our general rules were that each project required a technical lead, a data analyst, and a developer (either internal or outsourced). Each person could only work on two projects at once. As workload varied based on what step in the project life cycle they were in, personnel did become available for additional work in short windows of time. It was then that I could bring in a new project for a time until the resource had to jump back into one of their other two projects. This ebb and flow occurred constantly and it was my job to play God on who did what and when. I also relied upon a priority system set up by upper management. If I had to choose between projects, I would compare their priorities and make a decision. Of course, it never worked that simply. The priority system hosted categories of priorities and so many projects often possessed the same priority. This was stupid but inevitable in a bureaucratic state like Intel. Project Managers would push to ridiculous lengths to utilize my people and rack and ruin was threatened if I didn’t. It was annoying, but manageable. Sometimes keeping track of over thirty people made me a bit confused, so I was frequently reporting out my resource logic, writing on white boards, and working the team to see if they could just squeeze one more thing in. I tend to stay reasonably disciplined when dealing with these situations and had to say no a lot. However, I did try to stretch the system as far as I could until I could see my people get pulled into too many directions. It was always a fine line and someone was always there to second-guess whichever choice you made.

We succeeded in developing a lot of really cool tools, our reputation was back on track, and we were humming. I learned a lot more about the Agile development process and I started to feel like my head was above water. It took at least a year. I also sat in on a number of SAP training courses, but I must confess, it helped me little.

Getting back to the brewing problems, a re-org took place and caused some significant political blowback. My manager in Swindon had reported to someone in the U.S., but now, he had to report to another manager he loathed on site in the UK. My manager was very ambitious and had campaigned hard to report directly to our new Director in the U.S. His ambition and his ego could scarcely handle having to report to an Intel “lifer” who possessed a very bad reputation. This manager had a history of leaving bodies in his wake and thus created a lot of enemies in Swindon. The gossip was continually revealing that he had HR investigations ongoing for his behavior with past employees and his reputation as a back-stabber and manipulator was entrenched. From day one, my manager, David, and his manager, Brian played power games against each other, and each struggled to take the other one down. Just about every conversation I had with David was a monologue about the evils of Brian. David and I were friends but I wanted to keep a safe distance from the fray. Our team was doing well, Brian liked my team, and I never had to work with him closely enough to feel the effects of his reputation. My main beef with him was that he would not confront some of our most serious problems, especially with project priorities. That was more of a tactical frustration for me, though, so I was able to carry on largely unfettered despite the turmoil in Swindon.

Months later, David announced that he was leaving Intel and joining a company called Exigen which specialized in software outsourcing and consulting. They had recently bought out our outsourcing company in St. Petersburg and David likely got a good offer from Exigen as a result. Already, there was a curious entanglement developing that I couldn’t grasp just yet. Suddenly, Brian became my manager and a new set of uncertainties came to pass.

As David was nearing his departure, he called me and said something strange. He said, without being able to tell me more details, to have a “Plan B.” I started feeling a strange mood around our group about this, but couldn’t tell what he meant. I didn’t have much time to think about it since I was just about to start my 10 week sabbatical. Intel gives employees 2 months plus your vacation time off every seven years, so it was my turn to take advantage. I stayed in Russia for about a month, then went to the U.S., and then to Ukraine during my time off. It was then that all hell broke loose.

During my month in Russia, I started getting calls about people on my team leaving Intel. I was trying to keep a bit of distance from it since Intel largely requires you to stay away from work completely during your sabbatical. However, the more I heard, the more alarmed I became. One by one, some of our most skilled people began leaving… and they were going to Exigen. As it turned out, Exigen decided to set up an outsourcing center in Nizhny. Our outsourcer in St. Petersburg was the one who made it happen. The President was a close friend of David, so the whole situation started getting sinister. I couldn’t reach David, so I knew he was avoiding me. I guess our friendship was over at that point and it was all just business, as they say. Upon hearing of the exodus, our Director from the U.S. called me and commiserated with me about the growing disaster. He and I had always gotten along well and he committed to saving the team regardless of what happened and that I would be the one to stay on and fix it. Still, I had over a month to go on my sabbatical, so I had to grit my teeth and try to enjoy my time off knowing that my work world was falling apart. I probably had the worst sabbatical on record at Intel. I went back to the U.S. and then on to Ukraine, receiving reports almost every day about who else was leaving.

Finally, my sabbatical ended and I returned to work. Though not everybody who resigned left yet, I pretty much knew who would stay. We closed ranks and I reassured them that I would work “110%” to rebuild the team. Curiously enough, they seemed far less upset about the situation than I. I have to admit, I was devastated and shaken. I felt like I was betrayed by people I thought I trusted. Some of my best people and best friends left. I took it very personally. It was my greatest challenge to even show up to work each day. Still, I managed to keep a brave face and I think it helped the team feel like there was something worth staying for.

The most fundamental reason why people left is that they were terrified that all C#/.Net development would cease and that their true love would be taken away from them. Ironically, it was David who had brought SAP into the picture in the first place, and then caused all the ensuing turmoil. There were also rumors that the Nizhny team was inevitably going to be cut from Intel entirely. They felt it was better to leave now with an opportunity in hand than to get laid off later. This was never going to happen, but I think David had sown so much negativity into the group, that people were willing to believe anything. Another catalyst was the historical leader of the group, Dmitry. I was brought in to help him manage the team. He didn’t like it much but went along with it as best he could. Gradually, though, many outside Russia lost faith in his ability to take over after I left. I was only supposed to be there 18-24 months, but seeing that the team couldn’t afford my loss and being that I still loved being in Russia, I was asked to stay on longer than expected. Once Dmitry learned this, he started to make his exit plan. The consequences of this were very Russian. Russians are clannish and usually stay loyal to the alpha-male. A couple years before, Intel’s head of marketing in Moscow resigned and took half the marketing team with him. With Dmitry leaving, many who had worked with him for a long time felt like they should follow him to Exigen, too. He was only one factor, though. Some of the people who left had already broken ranks with him, but he still carried enough weight to help tip the scales for several people. The last bit of irony was that everyone that left swore up and down that David did not spearhead this whole thing. I found it hard to believe, but what was done was done.

So after the smoke cleared, here were the casualty figures. We lost 20 out of the 32 people we had on the team at the time. We lost a large chunk of our most valuable people. We were pretty much wiped out. Fortunately, a handful of key people stayed. I had a short list of the remaining people in my mind. If any one of them decided to leave, that would be the end and I’d have to give up. They didn’t (and are still there to this day), so I had hope that we could turn this thing around. Another consequence of this event was that our Director flew over to England and fired Brian on the spot. I guess David’s master plan was complete. Honestly, I didn’t cry over it. Brian had so much baggage around him that it was bound to impact me eventually. If we were going to start over, I guess a clean slate was the better way to go.

At that point, I was asked to put together a presentation about how we were going to rebuild and how we were going to get Commissions tool rewrite done. I spent hours preparing for it and then presented it to the Director, his staff, and some other key stakeholders. Without patting myself too much on the back, I really nailed the presentation and got approval to move forward. I had a great plan, but I still needed the gumption. Fortunately, I had it despite quite a bit of stress. It was all in my hands now.

I still remember holding our first group meeting after the exodus. Normally, the room was filled to the gills, but now, there were 12 people sitting there. It was surreal. I explained that I was given full authority by the Director to rebuild the team. I was given several headcount and could start interviewing. We had a big project coming up and we had to gear up for it. The team seemed to get on with it and morale was surprisingly high. (I have no idea why, honestly)

For over a year, we had been slated to take on the next monster project of IT. The global sales force needed a brand new commissions tracking tool and everyone wanted us to do it. After the draining of our team, I though that there would be no way in hell that we would retain it, but we did. It was supposed to be project managed out of Swindon with most of the business analysts coming from there, so it was still the most sensible plan to team them up with Nizhny developers. It was also the case that the U.S. management had determined that we only needed 8 developers for the project, so our team could easily absorb it. I was given some headcount to fill some specific skill gaps, but I was not given full license to grow the team back to its previous number. Intel’s financial situation was slipping a little and IT was cutting back a lot, so there was little funding in the company to fund development projects. We’d just get by doing Commissions and not much more. It wasn’t such a bad thing since Commissions was going to keep us plenty busy.

Since we were starting with a clean slate, I decided to do a few things differently when rebuilding the team. The biggest complaint from outside Russia was that we were always a black box, communicated poorly, and would hire people with no buy in from outside stakeholders. In the past, Dmitry was famous for hiring people without telling anyone, a big no no at Intel. Swindon would cry out at times, “Who the hell is that guy and where did he come from?” This was my first time hiring for the team, so I decided to invite Swindon people to join my interview team. Two of my best colleagues took me up on it and we began looking for four new developers. We let the Russian team determine the candidates’ technical skills and then myself and my colleagues would interview for their soft skills. In the end, we hired some very good people and we got buy in from a wider spectrum of stakeholders. Swindon had more skin in the game than ever before and it helped us work better together.

I won’t go into the hiring process more except just to say that it was difficult to find a communicative software developer, let alone a good English speaker in Russia. We made some compromises, but overall, our team was much more outgoing and hungry to contribute to Intel.

To continue with Commissions, the project launched quickly and stakeholders weren’t much interested in waiting for my team to recover from our strife. The best developer, Stas, who stayed with us, took the technical lead position and began plotting out how to develop the application. The Project Manager, Alan, came from Swindon. About three business analysts were also located in Swindon. Our key customer who administered commissions for most of the company also joined the team. She was located in Massachusetts. The BA’s wrote the requirements and also received a lot of input from HQ in California. The list was absolutely huge. I was quite nervous about whether our shiny new team would be able to get up to speed fast enough to make a visible contribution early on. Earning trust early is always a key advantage. It didn’t take long to see that we weren’t operating at a fast clip and rumblings from afar began to come my way as to why. We had less time to maneuver than a lot of other projects. Most often, we would set a deadline for a project, but it wouldn’t be a disaster if it was late since most projects weren’t calendar-sensitive. However, Commissions had to be released by the beginning of the following year (about 14 months away) because it was impossible to use two different commissions tools in one fiscal year. When we started adding up all our estimates for completing the list of requirements, our forecasted end date was WAY past January 1st.

Recall a while ago that I mentioned that HQ had estimated that 8 developers could get the job done. This guess came from a consulting company and the number stuck in the heads of everyone and couldn’t be dislodged. As the project progressed with our 8 people on board, we were not making much of a dent in the requirements list (called the backlog). That was the prompt for doing what too many companies do when problems arise,.. look for a head to lop off. That head was mine. At one point, the Director went on Windows chat and lambasted me for falling behind. That was an extremely unsettling event. He then pounced on me in a conference call with most of the worldwide stakeholders in attendance. He blamed me for not hiring more people to staff up the development team. I was taken aback since no manager at Intel was allowed to hire people without headcount approved for them. You can’t just hire people whenever you feel like it. I tried to remain calm and responded that I would be happy to hire more people upon approval. I guess that was my approval. Two people from Swindon called me afterwards wondering if I had survived the show trial and admitted that they would have crumbled to dust if it had happened to them. They were fairly outraged at what happened to me. Believe me, I felt like crumbling to dust, but I guess my skin was getting thicker over the years. I went ahead and opened new reqs for developers and started hiring more. It took me a long time to get over that dressing down. This is an area of improvement that I really want to work on. I actually think the Director felt like his butt was on the line more than anyone and I happened to be walking by when he decided to throw a grenade.

We brought on more people and grew beyond 8 developers for the project. Though we passed this imaginary line, stakeholders still felt that this should never have happened. I felt like I was carrying a Scarlet Letter after that. Eventually, though, people in HQ finally started seeing the light. Our chief sponsor in HQ left Intel and a new guy came along. We barraged him with explanations of why the resource estimate was completely off. He finally understood and agreed to expand the team even further. At its peak, we had 22 developers on the project. Four were added from India, four were added in the U.S. and our team grew to 16. People finally realized that I wasn’t so stupid after all.

We still got nailed repeatedly for going too slow. I agonized over this. It was clearly possible that we had too many new people on the team and that they weren’t up to speed. I held numerous conversations with Stas to figure out what was going on. He did his best to explain that they were creating a complicated but very powerful architecture for the application and that this would take time in the beginning. In the Agile process, the team estimates how much work they were going to do in a given week. Multiple times, we came up short. I instructed them to be more conservative on their estimates which helped a little, but the spotlight was still stuck on us. When we added the Indian team to the project, they were frequently outperforming us and it was noticed. We investigated further and found that they were skipping a lot of steps and straying from our standards. Once we trained them more, they started to slow down a little. Though it doesn’t sound like one, it was a victory for us. Perception is reality, as I’ve said before, and it looked better if both India and Russia were working at a similar clip. As a side note, I must mention that somewhere in this timeframe, the Project Manager, Alan, became so stressed out that he had to take sick leave and get counseling. That’s how crazy this project got.

Though pressure eased off a bit, it was still there. To combat this, we decided to let two external parties audit our code and our methods. At the time, Microsoft was bugging me a lot to come in and tell us how they could help us with our development. Of course, they were wanting to sell us something we didn’t want to buy, but I did work with their European Director to get them to review our work for free. (this was a long game, but it worked) When they looked at our code, they were extremely impressed and felt that we were on the cutting edge of design and code quality. The code was also highly maintainable. It’s a very important concept in software development. To be maintainable means that code can continually be added on to the design without making the architecture a mess. In the long run, this made development and updates go faster and make the code more bug free.

We then also contacted the head of the Agile Users Group inside Intel who was located in Arizona. He was considered to be the expert in the company on Agile software development. Our team admired him and wanted him to look under the hood. Upon review, he was amazed at what the team was doing. We got his blessing, too, so things were looking up. Needless to say, I beat the drum HARD to every last stakeholder about these two endorsements. The India team was even giving us good reviews, so this trifecta redeemed us in front of the entire organization. The pressure valve was finally released. We stood justified for our work and people finally got off our backs.

Regardless of quality of work, there were still more requirements than time. We had to start making some hard choices about scope. We had wanted to build both a client tool and a web tool for the application. The client tool was meant for the commissions administrators who needed a very fast interface. We needed the web tool so that we could make it easy for the salespeople to access it. We didn’t want to make them install a client tool on their laptops since it was a lot of overhead to make sure they set it up properly. This tool was going to thousands of salespeople and we feared that there would be a huge problem getting non-technical salespeople up and running without too much trouble. We started talking about canceling the web tool for the first release since the client tool had a higher priority to be released. The client tool was also easier and faster to build. I’m a personal enemy of releasing a client tool to the masses. Intel had too many of those littering our environment and most of them sucked. I really winced when we had to communicate this idea. I though there would be a huge backlash. While there was some whinging, we actually got the approval and overcame a big hurdle. We had also wanted to release most of the tool by January 1st. However, it was clear that we couldn’t do that either. We went back and started figuring out what we absolutely needed by what date. Our review showed that we only needed a specific portion of it released in January specifically for the commissions administrators. By February, we needed a little more, and finally not until March did the salespeople really need to use it. With that analysis, we re-planned our schedule and released the tool in stages. Oftentimes, users didn’t even notice that we were continually updating it behind the scenes since they couldn’t see missing features if they didn’t need them yet or even know that they would exist in the near future. It was a very clever plan and the backlog finally got under control for us. Once Q1 started, we phased out the old Commissions tool and phased in the new one. It occurred quite seamlessly. We even developed a very easy installation process for the salespeople and there was nary a peep from them about problems. The release was almost anti-climactic since it went quietly and successfully. Normally, we did a lot of celebrating when we released something, but I think all of us throughout the organization felt like there was just too much more to do to feel like the job was “done.” I left Intel in May of that year and we were still busy working on it. In fact, it continued for the rest of the year and even three years later, the team still has resources dedicated to it. All in all, it was a successful project and most of the salespeople at Intel today use the tool we made. I got to see a project from conception to release, bore the political burdens and overcame them, and got to watch a lot of talented people make something out of nothing.

Other Parts of the Job

While all the activities above were going on, some other activities were operating in parallel. Amidst everything, we kept a small SAP team on board, hired two new people for the effort, and actually began delivering SAP releases extremely successfully. The other activity was my extensive work with the team to improve their leadership and communication skills.

Despite the grand exodus and flight from the SAP monster, there were still three people left behind that wanted to continue doing SAP development. Only one was a permanent employee and the other two were college interns. None of them were programmers, so they felt no need to leave Intel like the others. We still had a Salesforce Automation project to complete and for whatever reason, our stakeholders let us continue with it despite the loss of resources. I managed to get approval to hire one of the interns and then go externally and get another person. This was all going on when I was trying to hire C#/.Net developers, so it was a trying time. I included growth in SAP development in my presentation to the Director and he let me move forward with that too. (I must mention here, as I just thought of it, that our Director, though mercurial, really loved the Nizhny site and wanted Intel Russia to be successful. He loved to visit Russia, drink tons of vodka, gamble, and play pool all night with my team, too. If he hadn’t felt this way, we would have probably been dead.)

At this point we now had two direct hires who knew the project and had been trained well in SAP and one new hire who had experience in a similar enterprise system but didn’t know SAP specifically. There are very few SAP people in Russia, especially outside Moscow, since the regional economies in the country are still quite behind the West. We hired the new guy because we felt he had good aptitude, a great attitude, and he was Stas’ brother-in-law. (that’s how it works in Russia. Intel Russia was full of family members) Mikhail was nothing short of miraculous. He learned SAP very quickly and even had to learn quite a bit of English along the way. I don’t know how he did it. The three of them plus one intern were actually able to produce an outstanding release and received huge accolades for their efforts. We were seriously under-resourced and we still got the job done. I’ve never seen such driven people in my life. Andrei and Katya worked tirelessly and it scared me a bit as to how hard they worked. Katya was only 22 and just out of college. She is still one of the most brilliant people I’ve ever met. All the planets lined up for me on this one. I got them most of what they needed, especially the political support, but the rest was all them. From that point on, IT started looking at my team as a very important part of SAP development in the company. Since we hired most of our people from one of the local universities, I worked closely with the professors there to put SAP into their curriculum. I also obtained $10,000 from our University Relations department to fund their startup costs. The news made the local paper and TV and to this day, the Higher School of Economics teaches SAP at their university. Again, humility evades me. I did all of that along with Katya. We really did something special.

Leadership and Communication

The other activity was building leadership and communication skills. This started before the exodus. I chose some of the top people in the group and offered the opportunity for anyone else who wanted to improve themselves to join. At least 12 people participated. First on the docket was presentation skills. I needed them to be able to communicate with their Western stakeholders better so that they would be taken seriously. I wouldn’t be there forever, so I couldn’t do all the talking for them. They would have to take care of themselves. With that, I rotated them through multiple sessions per week and had them practice making speeches and writing PowerPoint presentations. It was painstaking work. I had to break bad habits (Russians have terrible presentation skills. Their entire communications culture has been learned by watching aging Communist bureaucrats reading hour-long speeches that would bore anyone to death. I saw it everywhere I went.) I made them practice extemporaneous speaking, operations reporting, influence and recommendation presentations, etc. I also made them write PowerPoint presentations about their own areas of interest at work and taught them how to engage the audience and excite them to adopt their views. We went over and over and over on this until they were blue in the face. It lasted several months. I then invited a smaller group to read a book on Leadership. There were 18 chapters on 18 specific themes. We took one a week and discussed the topics in every meeting. It made a huge impression on them. One of my former colleagues told me, close to two years after I left, that they still held the speaking sessions. They call it “the Molinari Repetition” since they realized how important it was to keep practicing over and over. I was very touched. Even as several of the people were leaving during the exodus, they came up to me privately and said, “Please don’t take this personally, us leaving was not your fault. I will never forget the leadership and communications lessons you gave me. They were some of the best things I ever learned.” I guess it was good that they said this because it was the only thing that kept me from killing them!

Key Learnings

I learned soooo much during this job, I don’t know where to begin. At the very least, I learned how to work with a different culture and to overcome the added difficulty that always transpired. Everything was harder. People wouldn’t understand me, bad cultural habits got in the way, and an enormous number of problems emerged that had to be solved during my tenure. If I had had the same problems in the U.S., it would have been half as hard to fix. I learned persistence more than anything. Living in Russia, working in Russia, surviving in Russia always required an extra push. That’s why I came home so confident in myself since I felt like I could handle anything that came my way.

I really learned leadership. Even when everything looked doomed and people didn’t believe that things were going to work out, I still succeeded. Many times in the past, I had wilted when the pressure got too strong. I was able to get past those older barriers more effectively. I still have a long way to go, but I did get a lot of good hard, experience under my belt.

I also learned a lot about politics and doing really big things. The bigger the thing, the greater the politics. I learned to expect pushback whenever I was trying to do something new or challenging and I managed to navigate through the complexity, the personalities, and the blind corners.

I also learned a lot about software and Agile development. I’m still not very technical, but I understand how much of the process works. I know how to get into something new and learn enough about it to make a contribution and I know I can do it again.

Performance Review Accomplishments

These were the line items written in my performance reviews during the times described above:

- Project Management: Dave allocated resources and supervised several projects that completed successfully. Those included CRA, TDF, ISMC, FIRST, eSales, and MPES. Though Dave moved to EAS during the year, he continued to own the resourcing, outsourcing, and stakeholder management for all BAS projects since the local BAS manager was struggling to do it alone. He also drove TDF business stakeholders to accept the need to do a technical release in order to repay technical debt. Though controversial at the time, it has proved to be critical to the success of TDF. The impact of this is that the Nizhny team delivered quality applications to its customers and empowered the team to take ownership of the quality level of their projects. Without Dave’s vigilance and direction, most projects developed in Russia risked failure.

- Process Improvement: Dave diagnosed several problems with project planning within the CBS Prioritization Team (including NN). He worked with key stakeholders to create (actually re-formulate) a comprehensive “rules of engagement” that was ratified by CBS. As a result, all groups benefited from a dependable process that caused better resource planning, clearer expectations amongst groups, and a needed discipline so that operations could run more efficiently and with less frustration.

- Quality Improvement: Nizhny software quality was challenged during the year and Dave took strong measures to address the issue. Dave gathered important quality indicators, analyzed specific projects, and reported out results to upper management. This resulted in an improved assessment of NN’s reputation, but more work was needed to make quality a more proactive effort. Dave worked with stakeholders to build a comprehensive view of how quality should be measured and perceived. He drove an internal team to build a dashboard that measures key areas of success on an ongoing basis. While all is not finished, Dave has instilled an attitude within the NN team that quality must not only be committed to, but measured and proactively communicated to outside stakeholders. This will continually improve NN’s reputation and effectiveness into the future.

- Mentorship and Management Improvement: Dave created numerous activities for developing and improving employees’ performance to Intel values and enhancing management and leadership skills. Dave initiated a more comprehensive MBO planning process, developed a new culture that was created collaboratively with the team, and repeatedly mentored the team to contribute more proactively to their reputation and future. Dave conducted numerous leadership workshops with the management team and also created a communication program where several key team members were invited to practice their presentation skills every week in order to advance their ability to communicate to outside stakeholders. With these efforts, the team has begun to improve their strategic thinking abilities, have learned better ways to influence, and have honed their presentation and English skills.

Introduction

Introduction

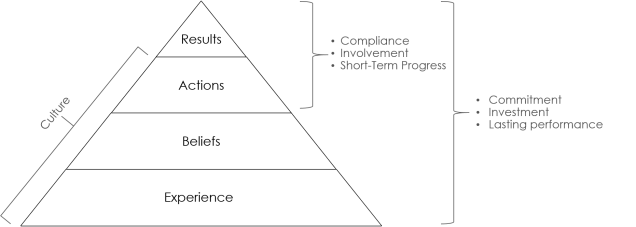

Change the Culture, Change the Game

Change the Culture, Change the Game

Below is a compilation of strengths noted in many of my performance reviews over the years. These comments crossed multiple jobs during my time at Intel Corporation. I edited the text to fix some of the choppiness and incomplete sentences that are normally used in a performance review document in order to save space. I did my best to preserve the messages intended by managers.

Below is a compilation of strengths noted in many of my performance reviews over the years. These comments crossed multiple jobs during my time at Intel Corporation. I edited the text to fix some of the choppiness and incomplete sentences that are normally used in a performance review document in order to save space. I did my best to preserve the messages intended by managers. In this classic text, Taiichi Ohno–inventor of the Toyota Production System and Lean manufacturing–shares the genius that sets him apart as one of the most disciplined and creative thinkers of our time. Combining his candid insights with a rigorous analysis of Toyota’s attempts at Lean production, Ohno’s book explains how Lean principles can improve any production endeavor. A historical and philosophical description of just-in-time and Lean manufacturing, this work is a must read for all students of human progress. On a more practical level, it continues to provide inspiration and instruction for those seeking to improve efficiency through the elimination of waste.

In this classic text, Taiichi Ohno–inventor of the Toyota Production System and Lean manufacturing–shares the genius that sets him apart as one of the most disciplined and creative thinkers of our time. Combining his candid insights with a rigorous analysis of Toyota’s attempts at Lean production, Ohno’s book explains how Lean principles can improve any production endeavor. A historical and philosophical description of just-in-time and Lean manufacturing, this work is a must read for all students of human progress. On a more practical level, it continues to provide inspiration and instruction for those seeking to improve efficiency through the elimination of waste.